Era, era on the wall, which was the greatest of them all?

Era: (n) A long and distinct period of history marked by character, events and changes

×

Right ▼

Pivotonians v Redlegs at Corio

×

In the midst of what history will surely judge as one of football’s darkest periods – consumed by issues of tanking and doping, media saturation, broke clubs, broken players, wealth divides, conflicts of interest, League manipulation, fan consternation and a tactically obsessed, coach-driven style of game – casting a nostalgic glow over simpler times is a natural inclination.

Looking back to move forward isn’t a complete waste of time either.

For there’s no time like the present to reflect on what made the AFL the juggernaut it is and forging a path to a fan-focused place that embraces all generations, the uninitiated, the disenfranchised and the rusted-ons.

×

Left ▼

1930 Football Record cover - advertisers knew their market.

×

Such introspection isn’t new. Leonie Sandercock & Ian Turner’s 1980 tome Up Where Cazaly? laments the corporate hijacking of the VFL harking back to the 1960s. And football identities back then were concerned too much money was polluting the purity of the sport and its participants.

Never mind the messy business of money and other matters, determining when we reached ‘peak football’ is an interesting exercise in itself. There are so many objective and subjective indicators of good health besides crowd numbers, TV ratings and club membership, such as evenness and unpredictability, game aesthetic appeal, scoring, skill level, physicality, fan engagement, grass roots participation, inclusiveness and diversity.

And of course the number of wins experienced by one’s team on the field tend to mitigate the acceptance of losses off the field.

So, with apologies to SANFL & WAFL aficionados, this nine part series will examine the good, the bad and the ugly of nine distinctive VFL/AFL eras.

First we’ll park the Delorean at a distant time when footy lifted its game to a more definitive style which appealed to a mass audience.

PART 1 – Well oiled machines (1925 – 1938)

It took a good number of decades before Australian Rules found its feet, so to speak. The early evolution of footy was slow and incremental; two steps forward, one step back. Without much footage to speak of and reliance on sketchy anecdotal accounts, we’ll begin this exercise in the mid 1920’s when scoring picked up and greater method was applied to a chaotic code which uniquely boasted no off-side rule.

×

Center ▼

Footscray's VFL debut at the Western Oval

×

What might be dubbed ‘footy’s awakening’ coincided with VFA clubs North Melbourne, Footscray and Hawthorn being admitted to the VFL, bringing the number of clubs to a nice even dozen. However the Australasian wasn’t so nice, saying the ‘rape of three clubs was as shameless as it was unfair’. Indeed the greatest threat to the VFL was not soccer, rugby or any other sport but the VFA. The bitterness between the duel competitions grew. And it must be said the Association led the way in bettering the game with effective rule changes that would subsequently be adopted by the League.

×

Left ▼

The VFL team that played the VFA in 1931

×

In that regard the 1925 VFL season heralded the introduction of free kicks against the last team to have touched the ball before going out of bounds.

And, as is still the case, the interpretation of the holding the ball law caused great debate – especially in 1930 when the previous ‘dropping the ball’ rule was reinstated mid-season to avert scrimmages and encourage free-flowing ball movement.

With the addition of spearheads Coventry, Moriarty, Moloney, Vallence, Mohr and later Todd and Titus, served by rule changes and faster play, scoring steadily climbed from an average of a measly 69 to a gratifying 92 points per team per match. A 1931 encounter in which St Kilda and Collingwood both kicked 20 goals saw Coventry and Mohr both bag 11. Finals were no barrier to goal sprees; ‘Soapy’ Vallence kicked 11 twice in final and Coventry nine in the 1928 decider.

“The players recognise that in their own interests, as well as that of the side, the ball should be kept moving without delay.”

–

The Australasian, 1930

×

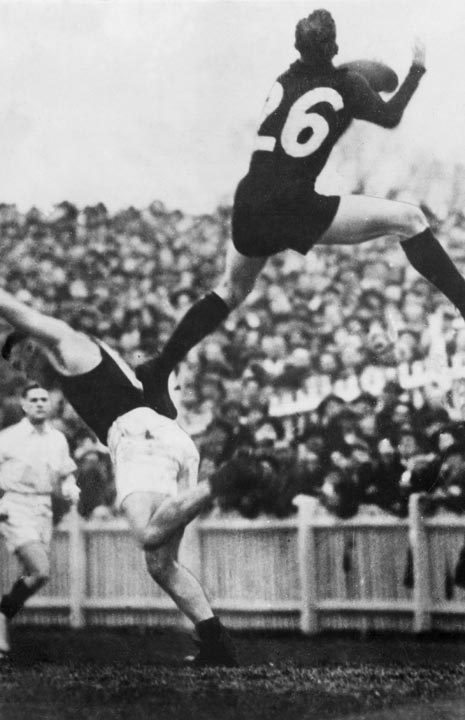

Right ▼

Ron Todd flies high

×

The onset of the Depression saw the game prove the most popular of diversions. Although the official VFL journal Football painted a rosy picture that the game provided a ‘clean and wholesome entertainment for the edification of the people’, cross-town rivalries were etched in blood amid brawling on both sides of the fence. With unemployment at 30%, a degree of frustration is perhaps understandable.

Yet despite the financial woes that affected so many, attendance averages remained steady around the 17,000 mark. VFL secretary L. O’Brien wrote that while other amusements increased their charges, not so the VFL. It was still the ‘cheapest and most spectacular amusement offered to the public’.

It must also be said the emergence of high fliers and prolific goalkicking targets provided better entertainment for a wider audience, even if the suburban sardine cans (which tended to smell worse than a can of sardines) were often as full as the rollicking cable trams that transported them there. You may not have a job but for less than the price of a beer you might enjoy the fleeting intoxication of winning on a Saturday arvo.

And no club won like Jock McHale’s Magpies (which granted free admission for the unemployed). The Woodsmen brought a new level of team orientated determination to the table. ‘The Machine’s’ 4-peat has yet to be repeated, whilst six flags from 10 grand finals over 14 years cemented Collingwood to this day as the most famous, the most loved and the most reviled football club of any code in the country.

“Big cricket is a great drawcard in Melbourne , but football is a religion, affording food for thought as well as for talk all the week.”

– The Australasian, 1930

×

Left ▼

Bob Pratt kicked 150 in 1934

×

Whilst the Carringbush’s dominance was predicated upon the menacing presence of Albert Collier, the ground-breaking century goal-kicking feats of Gordon ‘Nuts’ Coventry and their Brownlow winning siblings Harry and Syd, South Melbourne assembled a ‘foreign legion’ of stars from Western Australia. The Bloods’ spectacular focal point Bob Pratt was nigh unstoppable in his prime, as was versatile champion Laurie Nash. South were the first club to attempt an instant dynasty, and whilst they short changed themselves on silverware they ignited crowds and took the game to a new level of excitement.

In between the Bloods and the Pies’ dominance the Tigers snagged a couple flags and became a popular attraction with the Strang brothers and the inimitable Jack Dyer in the ruck. Individually, Fitzroy and Essendon had Bunton and Reynolds as wunderkinds to lure their fans through the turnstiles.

The era wasn’t all bags of goals and speckies. New additions to the ranks in North and Hawthorn were largely uncompetitive. There was no means of equalisation and clubs were left to their own devices. The die was already being cast as the best administered clubs with the most success and largest support bases future proofed themselves against the ravages of on-field failure.

Having endured and thrived through the Great Depression, football’s development suddenly faced a larger threat. More on that in the next instalment…

The era in film and pictures

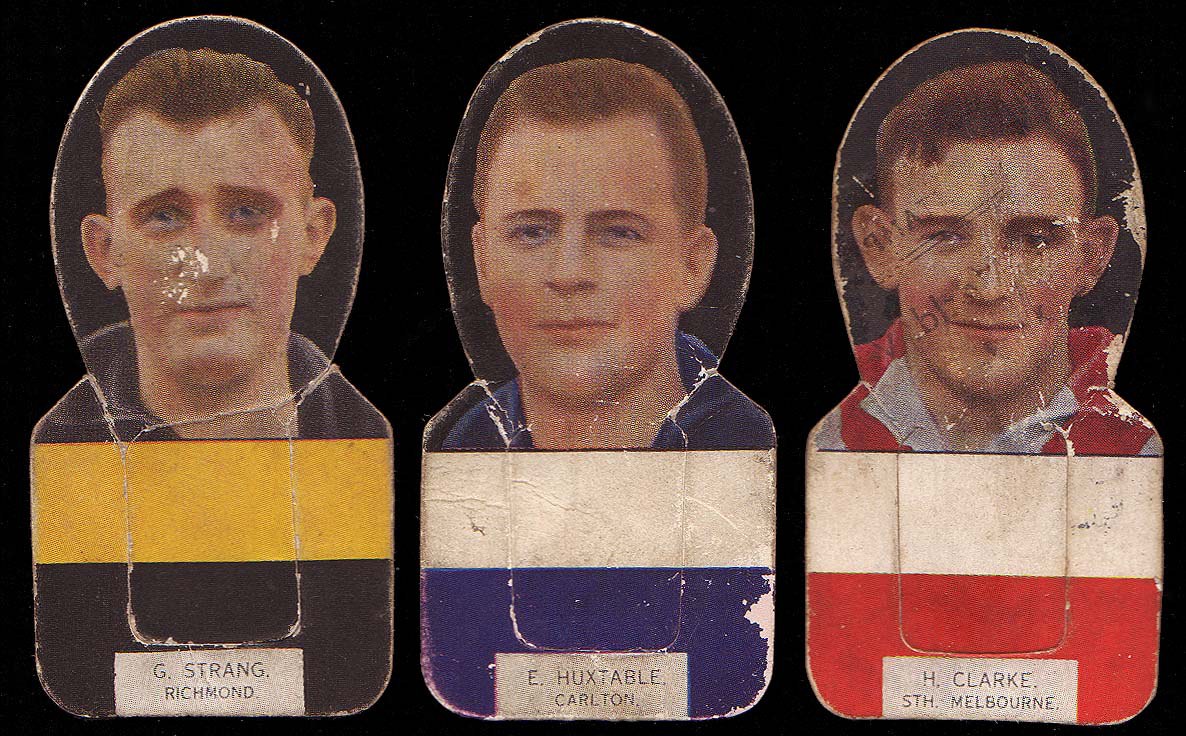

Center ▼

Cigarette cards

×

Center ▼

Gordon Coventry marks against Melbourne

×

×

Center ▼

Capstan, Havelock and Tuef were the cigarettes of choice

×

×

Center ▼

As they lined up in the 1935 Grand Final

×

×

Center ▼

Carlton's Jim Park at Princes Park

×

×

Center ▼

The great Laurie Nash

×

×

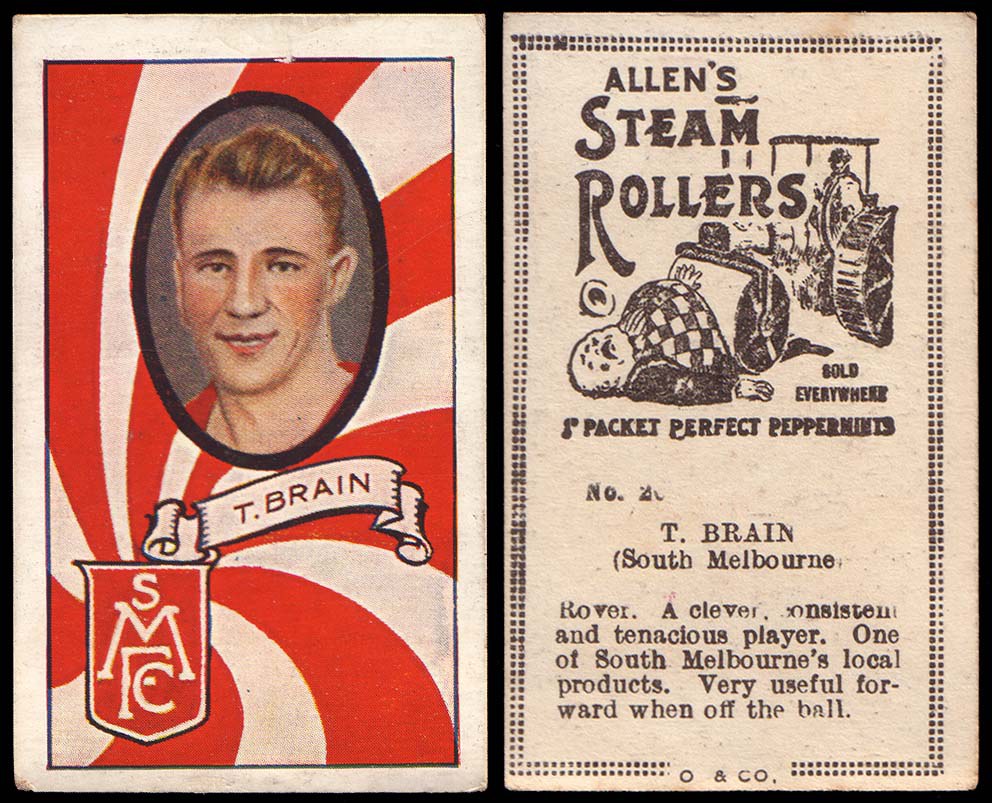

Center ▼

Remember Allen's Steam Rollers?

×

×

Center ▼

The 1937 Grand Final

×

Center ▼

+

Footnotes

Videos sourced from YouTube, courtesy of 1980's VFL Football and Rob M.

Comments

Julien Peter Benney 19 August 2015

The unbalanced competition in the VFL in the late 1920s and 1930s, as historians have shown, reflects the fact that only a few clubs (Carlton, Collingwood and Richmond) had the patrons needed to professionalise - with the result that most of the remaining clubs opposed a fully professional league that was possible much earlier than people realise. "Up Where Cazaly" points this out, and how Hawthorn and St. Kilda, especially, were devoid of business patronage and could not be competitive for decades after this.

It seems to me that without the Coulter Law the few big VFL clubs would have come to monopolise the sport's best players later in the Depression years, in the process taking many more players form the WAFL and SANFL than they did. The VFL realised that the competition was becoming monopolised by a few clubs with the Coulter Law of 1931 - which set player payments at no more than three pounds per match, far less than Carlton and Richmond could pay. It has become clear to me that, although it did so SLOWLY, the Coulter Law did reduce the rate of transfer of interstate recruits very substantially, although it did nothing to make Hawthorn competitive - something which was not achieved until League revenue-sharing began to have an effect in the middle 1950s.

Login to leave a comment.